Statutory supervision of midwifery has been in place in the UK for 113 years. Recently, however, the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC, 2015) have voted to accept the recommendations of the King's fund review (2015) into midwifery regulation, which will see the end of the statutory supervision of midwifery as we know it. Much of the literature on this subject extols the virtues of statutory supervision. The aim of this study is to explore current perceptions of statutory supervision among a sample of midwifery practitioners to establish whether their views and opinions of statutory supervision supports or undermines the provision of care. The data represents a complex picture of supervision. Concerns and challenges arise for all those involved with statutory supervision, which at times does not appear to support the provision of quality care.

Statutory supervision of midwifery has been part of the regulatory framework for midwives since the Midwives Registration Act in 1902. The aim of this framework is to safeguard women and their babies by supporting midwifery practice (Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), 2011). However, as a result of concerns about supervision raised by the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO, 2013), statutory supervision of midwifery has been under scrutiny throughout 2014 by the King's Fund. On 28 January 2015, the NMC voted unanimously to accept the recommendations that were part of the King's Fund review of midwifery regulation (Baird et al, 2015). The core recommendation of this review was that the NMC should have sole responsibility and accountability for the core function of regulation. Once amendments have been made to the Nursing and Midwifery Order (2001) by Parliament, statutory supervision by the NMC will cease to exist. Throughout this meeting, individuals in the audience and members of the NMC council voiced their approval of the supervision of midwifery and the many perceived benefits it provides to the profession and the pregnant woman and her family. These comments were interesting given that the reason for the King's Fund review were the flaws in statutory supervision that had been recognised by the PHSO (2013) and which called for changes to be made to the way that the regulation of midwifery was undertaken in the UK.

The literature has frequently identified the positive impact that supervision has on practice (Duerden, 2002; Carr, 2008). These advantages include: support for both midwives and pregnant women, public protection and leadership. However, the potential for problems and tension within the supervisory structure is also documented (Kirkham and Morgan, 2006). Henshaw et al (2013) found that midwives' opinions of the nature and role of supervision were varied. They additionally note that there was limited evidence that demonstrated that supervision promoted patient safety and quality care. The King's Fund review (2015) similarly found that there was limited evidence to demonstrate that supervision prevented midwives being referred to the NMC for fitness-to-practise issues, although the report recognised that this lack of evidence was, in part, due to limitations in the NMC's own data collection processes. This lack of confirmation that supervision facilitates safe practise is problematic given that issues in the provision of care in maternity services still exist (Knight et al, 2014) and claims of negligence and litigation continue to rise (National Health Service Litigation Authority, 2013).

This study is part of a doctoral study, which examines the current regulation of midwifery and includes: an exploration of statutory supervision, clinical governance and midwives' perception of the regulatory authority of the NMC.

This study offers a socio-legal exploration of midwifery governance and legal frameworks (Fitzpatrick, 1995; Cotterrell, 1998). Ewick and Silbey (1998) suggest that socio-legal studies may be defined as the exploration of the function of law in shared societal situations in an attempt to understand the influence that each has on the other, in this instance, the impact that regulation has on midwifery practice. At the onset of this study the interest focused on the way in which midwives perceived governance, its impact on their practice and the relationship between the pregnant woman and the midwife. By employing a strategy that examines the ‘lived experience’ of the subjects, their understanding of regulation and its influence on the role of the midwives participating in the study may be described and analysed (van Manen, 1990). The study was carried out between March 2012 and March 2013 and included midwives who worked in both the NHS and private sectors in the South East of England.

The sample aimed to recruit midwives with a diverse range of experiences of regulation. Participants varied in the length of time they had been qualified, whether or not they were a supervisor of midwives, the area in which they worked either as an independent midwife or within the NHS, and whether or not they had any direct experience of supported practice within the statutory supervision of midwives framework. For those midwives working within the NHS, the criteria also incorporated midwives with a range of experience from the most junior to the more senior in positions of management. As a consequence of providing such a broad sample it was anticipated that the findings might then be more relevant and applicable to the wider population of qualified midwifery registrants working in the UK.

The study gathered quantitative data via an online survey. An invitation email was sent to potential participants that contained information about the research and a link to the online survey. The invitation email provided the participants with the opportunity to contact the researcher via email if they wished to take part in a follow-up semi-structured interview. The online survey, which was constructed using a secure server and which encrypted responses, did not contain any names of participants or any other identifying information, and as such facilitated confidentiality and anonymity of the participants.

The study also collected qualitative data using face-to-face semi-structured interviews which began in November 2012. Four pilot interviews were conducted drawing on contacts and associates known to the researcher (Kvale and Brinkmann, 2009). This permitted the testing of the interview schedule to determine whether it was fit for purpose. As a result some of the questions were refined so that the data that would be generated could be used to explore the research question in detail. The format for the interviews was then replicated in subsequent interviews.

Ethical approval for this study was sought and gained from the University of Kent Law School Research Ethics Advisory Group; East Kent Hospitals University Foundation Trust Research and Development Department and Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust Research and Development Department in accordance with the NHS National Research Ethics Service guidance.

The analysis of the data was commenced soon after the online survey and semi-structured interviews were completed. The interviews were transcribed verbatim and coded prior to analysis of the data. The data from the online survey were examined and considered in terms of how the participants responded in the semi-structured interviews and where possible the two were contrasted, which enabled a detailed picture to be constructed. All information derived from this process including information about individual service users was anonymised to help to maintain confidentiality (Hennink et al, 2011). This was continued throughout the analysis of data and in the presentation of results through the use of pseudonyms when direct quotes from participants are employed. The analysed data was grouped into themes that arose from the transcripts which appeared to be directly related to the focus of the research (Bryman, 2012). As a result of this process several key themes emerged including woman-centred care; accountability; and safe and effective care provision.

Online survey The online survey was distributed to a sample of 192 midwives working within the NHS or as independent midwives in the South East of England and achieved a response rate of 70%. This response rate would appear to indicate that the topic was important and one which participants had opinions and views on.

The online survey was divided into three sections which examined:

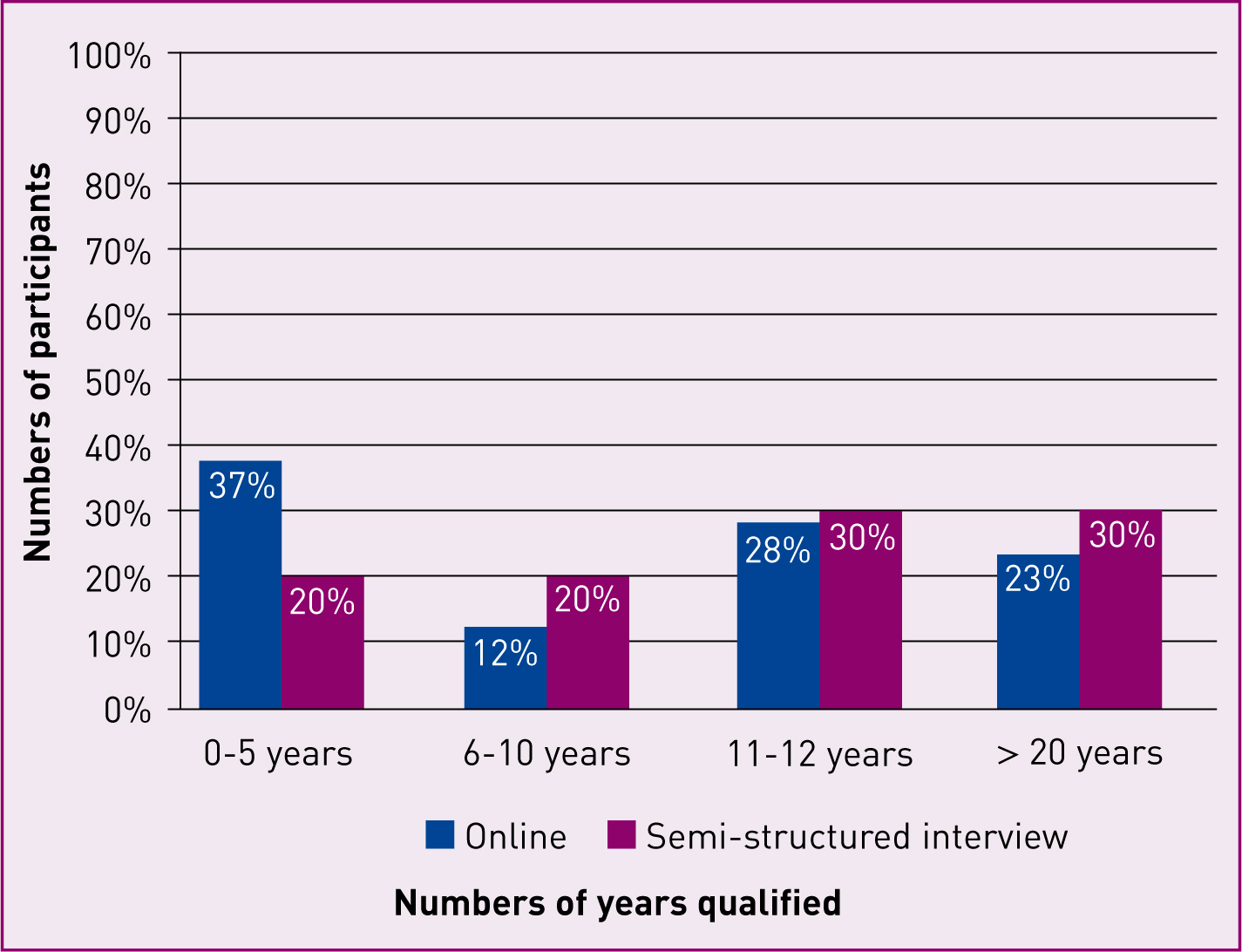

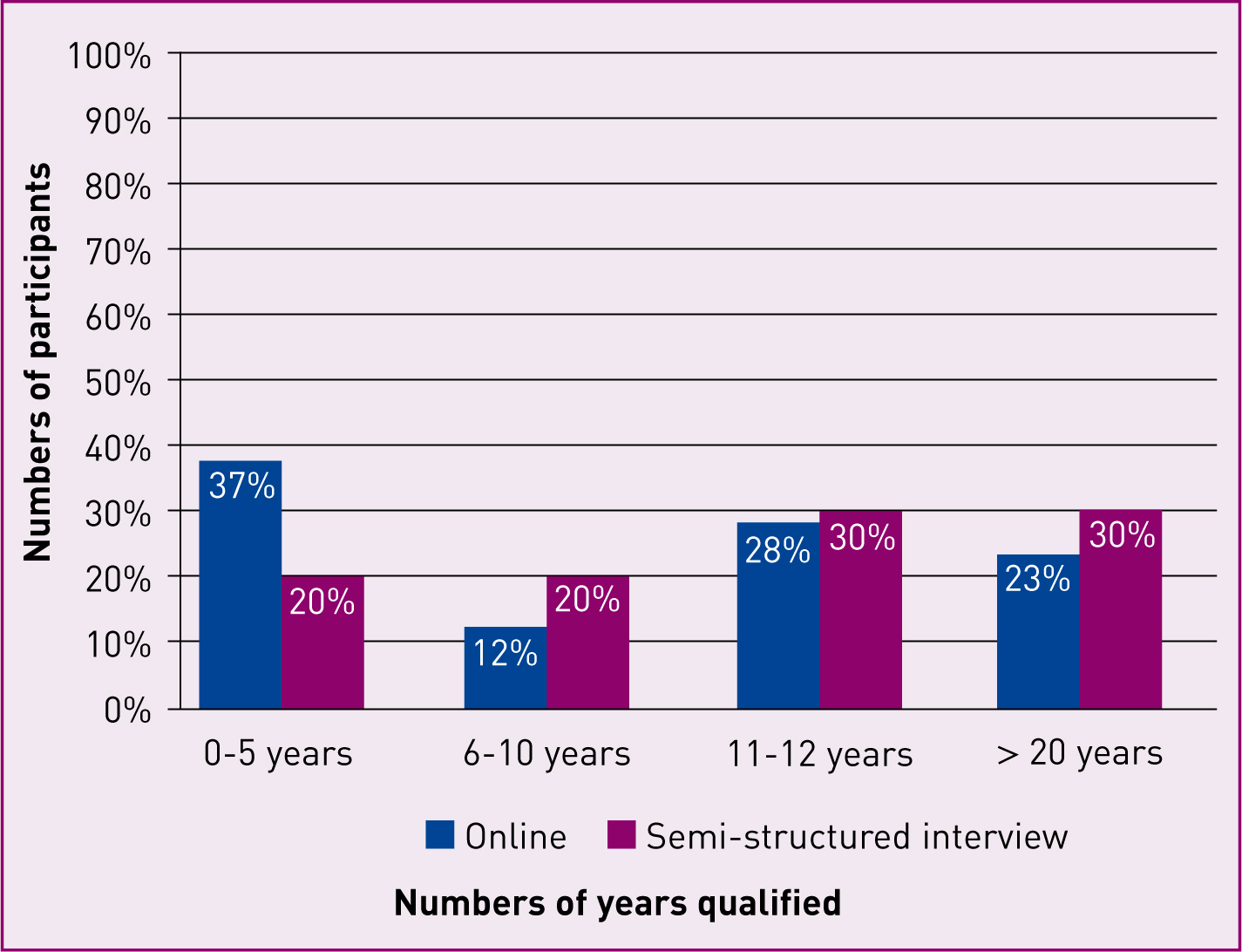

The demographic of participants who completed the online survey was as follows: 95% of respondents were employed within the NHS and the remaining 5% of midwives were either working currently in independent practice or had recently been engaged as independent midwives. While these figures are disproportionate to actual numbers of independent practitioners in the workforce, where it is estimated that only 0.4% of midwives are employed independently in the UK (Department of Health (DH), 2014), in this study the over-representation of independent midwives was a deliberate and important strategy as these practitioners were likely to offer a different perspective of governance and regulation. Additionally, 51% of the sample who worked in the NHS practised in the acute hospital environment and 42% were working in the community setting. These figures reflect the large geographical area over which care is provided in the South East region of the UK which includes both urban and rural locations. Figure 1 shows a representation of the comparison of participants in the online survey and semi-structured interviews.

As a result of conducting this quantitative research, areas of concern and interest were identified which were then explored in more detail in the semi-structured interviews.

Twenty semi-structured interviews were conducted. Eighty-five percent of the sample were employed within the public sector whilst the remaining 15% were currently, or had recently been, engaged as an independent practitioner. As with the online survey, there was an equal representation of midwives in the NHS who were practising in either the acute hospital setting (51%), or the community environment (49%). Within the sample, 20% were supervisors of midwives, this is somewhat higher than the NMC (2013) estimates. However, it was felt that participants with direct experience of the statutory supervision of midwifery framework might offer some valuable insights compared to midwives who were not supervisors of midwives. It was felt that the inclusion of four supervisors, although a small sample, would help to produce a balanced view of the supervision of midwifery from the supervisor's perspective.

The themes that emerged out of both the quantitative and qualitative data included:

In general terms there was support for supervision of midwives both in the online survey and in the semi-structured interviews. Within the semi-structured interviews some participants were positive towards statutory supervision:

‘It's about promoting optimal practice.’ (Lilly: band 5 midwife)

‘Supervisors are there to support and help and guide and protect.’ (Megan: band 6 midwife)

However, others were less confident about the purpose of supervision

‘It's very destructive … I don't think it's functional.’ (Laura: independent midwife)

‘It's a bit of a policing activity.’ (Lucy: band 7 midwife)

Six percent of respondents in the online survey mirrored the last comment and felt that statutory supervision was a mechanism for the policing of midwifery. When examined in more detail, the apprehension about the purpose of statutory supervision and its ability to ensure safe practice was reflected by several other participants. Throughout the semi-structured interviews, the participants raised concerns about the ability of statutory supervision to ensure safe effective care for women particularly in relation to the expertise of the supervisor. The disparity in the competence of the supervisor of midwives was recognised by several of the participants.

‘There are some supervisors of midwives who are exemplary and others who are not.’ (Amy: SoM)

‘It depends on the individual supervisor, they're all trained the same but it's how they use those skills and that knowledge.’ (Megan: band 6 midwife)

As a consequence of the changing nature of midwifery practice, midwives have by necessity needed to develop skills and expertise in areas previously unfamiliar to them. In these situations the current on-call system for supervision was undermined for a number of the midwifery participants in some circumstances as a result of the lack of clinical expertise and support that the supervisor was able to provide. Some participants noted:

‘If you had supervisors who had some degree of expertise you would know how to use them. They're meant to be expert midwives; well I would suggest that some of them aren't expert in certain areas at all.’ (Amanda: band 8 midwife)

‘There's no point having a fantastic labour ward midwife supervising a community homebirth midwife, that's just not helpful … I use my supervisor for her knowledge and to be able to talk things through with her so there's no point if she's not got an area of expertise that's shared.’ (June: independent midwife)

When this feature of the regulatory framework was explored, a picture emerged suggesting that there were some difficulties with the annual review. These concerns were centred on the purpose of the annual review and whether it supported or undermined practice. For some midwives who were supervisors, the lack of consistency was identified as being problematic.

‘There's a bit of poetic license with reviews … we have a set format which involves looking at mandatory training, auditing notes … but I like to personalise the review … I like to see what's achievable for the midwife in the review … so it depends on the supervisor I would say …’ (Tanya: SoM)

‘The yearly supervision meeting can be more of a chit chat … from speaking to different colleagues I would say it depends on who your supervisor is as to what the point and benefit of the meeting is …’ (Susan: band 7 midwife)

Other participants highlighted the perceived similarities between the annual appraisal and supervisory review:

‘It's difficult to distinguish between the appraisal process and the supervision process … the paperwork tends to be very similar, I think you're ticking two boxes for the same things …’ (Ruth: band 6 midwife)

‘The annual supervisory meeting is a bit of a check list … when nurses go through their level of competence they do that with their manager. So one could argue that you're doing similar things but under different guises.’ (Louise: band 8 midwife)

‘Midwives worry about the annual review because they're not confident in their practice … and if the wrong people are supervising and managing them and using their authority as a disciplinary measure rather than a supportive measure … well that's not how supervision should be, the supervisor should be there to help you to improve your practice, to identify what you can do to improve your practice and to support you through what you've done in the past.’ (Megan: band 6 midwife)

When questioned about experiences of supported practice, 60% of participants in the on-line survey thought it was beneficial to their practice while 40% did not. These figures replicate some of the reservations that participants had in the semi-structured interviews:

‘I think sometimes it's the judgement call of the supervisor who is making that decision … two supervisors can think differently about one incident … I have seen some inconsistent decisions … where it's done more damage to the midwife.’ (Jean: band 6 midwife)

‘It's as good as the individuals that are involved and it varies hugely and it's not particularly consistent … because everybody seems to have a slightly different way of how they do things … and that's not safe.’ (June: independent midwife)

‘How do I know what I'm doing is what I should be doing … You don't know, you only know about it if something really went wrong … that erodes the purpose of supervision and risk assessment, because the whole point is that you try and avoid something happening … if the only time when anything is flagged up is when it's gone really wrong, then that defeats the whole object of supervision.’ (Susan: band 7 midwife)

Some midwives when discussing experiences of supervisory investigations were unsure of the robustness of the process.

‘The investigation didn't find that I'd done anything wrong … I would understand if I had … but it was traumatic … it wasn't fit for purpose, it was just a tick box exercise … even my own supervisor said so …’ (Paula: independent midwife)

‘The incident that was investigated hadn't happened to me before so it wasn't something I could improve on… nobody told me how they made the decision…’ (Cathy: band 5 midwife)

In the online survey, 81% of respondents stated that they felt that nursing should have statutory supervision and 69% believed that not having statutory supervision had a negative impact on the nursing profession. This positivity was mirrored by some participants in the semi-structured interviews:

‘A nurse can make mistakes the same as a midwife … so the advantage would be knowing that somebody is there to support you should you need them.’ (Karen: band 6 midwife)

‘They [nurses] only have a disciplinary rule which doesn't support the profession … the general public don't have recourse to the mechanism of supervision so they have to go straight to the NMC if they had any concern …there isn't a local mechanism.’ (Kate: SoM)

However, other participants were more sceptical about the perceived benefits of statutory supervision for nursing:

‘Nursing has managed without statutory supervision up until now … I think to be honest clinical supervision should be enough.’ (Louise: band 8 midwife)

‘Maybe we just need a framework of clinical supervision … I think statutory supervision is just not effective.’ (Laura: independent midwife)

‘Having statutory supervision would appear to be negative for midwifery because when you look at NMC hearings you would expect not to see many midwives before fitness to practise panels … and these hearings are for common things which you would not expect to see if supervision was working.’ (Mary: SoM)

In much of the data, the theme of supervision and its ability to facilitate woman-centred care was raised. For some participants there was an integral connection between supervision of midwifery and the promotion of individualised care.

‘Supervisors of midwives can affect the careers of midwives and the woman's birth experience too and make it better … if I as a supervisor can support the midwife then she supports the woman.’ (Samantha: SoM)

However, some midwifery participants were less confident that statutory supervision supported the pregnant woman especially in relation to the woman's ability to make decisions about her care.

‘Supervision may be used with women who want to challenge the establishment … they might not meet the criteria for a homebirth but they are adamant they've understood!’ (Tanya: SoM)

‘The effect of supervision can be strangulation … forcing the woman to have care that she doesn't want … that's not the proper care we should be giving. We should be giving holistic care … but when supervision is involved and care is strangulated because midwives are scared … then that's to the detriment of the woman…’ (Lucy: band 7 midwife)

‘I had a woman who didn't want to be transferred in … she was in labour and was determined that she was going to stay at home, although the labour was delayed … So I phoned the supervisor and she agreed that the woman needed to come in and because I told the woman that the supervisor said she had to come in she changed her mind and went in …’ (Jean: band 6 midwife)

While many midwives were broadly supportive of supervision as a regulatory mechanism they were unconvinced that it necessarily ensured safety in practice, practitioner accountability and facilitated woman-centred care. The benefits of supervision are recognised by midwives and supervisors in the literature (Halksworth et al, 2000). However Stapleton et al (1998) found that some midwives had experienced poor supervisory support which resulted in limited access to a supervisor in times of need. Ball et al (2002) similarly found that ineffective supervision impacted on the provision of support in practice. When discussing the supervisory relationship,Williams (1996) established that the personal skills of the supervisor were pivotal to an effective partnership. Stapleton and Kirkham (2000) recommended that supervisors should have a range of interpersonal attributes, which include being caring, and having broad knowledge and experience in clinical practice. Midwives in this study acknowledged the problems that non-expert supervisors posed particularly in challenging situations.

Different styles of implementing the annual supervisory review were also identified by the midwives. McDaid and Stewart-Moore (2006) found that the annual supervisory review, in some instances, rather than facilitating good practice appeared to widen the gap between the supervisor and the supervisee. Conversely Kirkham and Morgan (2006) were more positive about the annual review. Midwives in this study expressed their concern about the inconsistency in the annual supervisory review. This is interesting given that there are currently prescribed Local Supervising Authority (LSA) guidance (Wallace, 2013) which aims to ensure consistency across the various LSAs in the UK.

The difficulty with inconsistency in supervision also emerged in the data in relation to supervisory investigations into incidents in practice. Stapleton and Kirkham (2000) found that some midwives felt disempowered by supervision, particularly in terms of local supervisory decisions. The supervisory investigation should follow a clear and transparent process (Porteous, 2011) and should be managed according to the framework prescribed by the regulator (NMC, 2012). Midwives in this study, particularly those who had personal experience of supervisory investigations, felt that the process was subject to the discretion of the individual supervisor, and as a result these midwives did not believe that the experience had enhanced their practice.

Within the study the concept of accountability arose when participants compared the model of clinical supervision with statutory supervision. Deery (1999) maintains that statutory supervision enhances the provision of safe care, a position which is echoed by others in the midwifery literature (Henshaw et al, 2013; Hodgson, 2014; Roseghini and Nipper, 2014). Clinical supervision is likewise seen as a mechanism of support for the nursing profession (Spence et al, 2002), while also being recognised as an integral component of quality care provision for other health care professions (Falender et al, 2014). Many of the participants in this study questioned the efficacy of statutory supervision with regards to professional responsibility and its ability to ensure safe quality care for women and their families. Given that other health professionals do not rely on the same statutory mechanism when providing care, the continuation of statutory supervision for midwives would therefore appear questionable.

‘The time has come to examine supervision of midwifery and to develop a framework of support in practice that promotes quality care provision, while being freed from statutory constraints.’

The last theme which emerged from the data related to the supervision of midwifery and the provision of woman-centred care. Freemantle (2013) suggests that there are tensions and conflicts within the maternity services, which often take precedence over the woman's needs and the midwife's ability to facilitate the woman's care. In these circumstances, clinical governance and supervision are employed to control the provision of care (DH, 1998; Duerden, 2002). The difficulty with statutory supervision in the context of woman-centred care appeared to be challenging for several midwives in this study as a result of service issues and the pregnant woman's expectations. This was considered to be particularly problematic when the woman's chosen plan for her pregnancy and birth was not compliant with service provision and current guidelines. Symon (2006) suggests that the difficulty with guidelines that attempt to standardise care is that they are based on population data and do not take into account the needs and expectations of individual women. Current guidance for statutory supervision recommends that the supervisor should support both the midwife and the pregnant woman while adhering to local NHS guidance (Smith, 2013). In the data, however, it would appear that in some situations the supervisor of midwives is expected to tailor the pregnant woman's needs and expectations to the demands of the service, or in some circumstances constrain rather than endorse woman-centred care.

Supervisors of midwives have long claimed to lead the profession, while supporting quality care provision. This study has highlighted that supervision of midwifery, while being broadly supported by midwives, is not without its difficulties. As the NMC have now agreed to accept the recommendations of the Kings' Fund review (2015), it could be argued that the time has come to examine supervision of midwifery and to develop a framework of support in practice that promotes quality care provision, while being freed from statutory constraints. The concept of supervision is commendable both in terms of the safety of the public and the support of the midwife. This study has demonstrated that there are supervisors who currently have a wealth of experience and knowledge, and that there are midwives and women who value the support that is provided to them by these supervisors. In a post-statutory supervision era any new framework would need to ensure that the twin aims of public safety and support are maintained. Reform of supervision would therefore need to ensure that the skills and expertise that have been acquired by those supervisors of midwives who are expert are retained and utilised to address the duplication, confusion and tensions that currently exist across the range of regulatory mechanisms. This is particularly important in the areas such as the annual appraisal, provision of services and the facilitation of woman-centred care.

Any future regulatory structures devised by the NMC for midwives would need to ensure that safety in practice and the investigation of poor practice are robust and effective. The replacement of local supervisory investigations by the NMC procedures would therefore need to recognise the challenge of ensuring that these processes are fair, reasonable and thorough, and make certain that the new strategies to determine poor practice are fit for purpose. The King's Fund review (2015) identified that the NMC has limited data on its fitness to practise procedures. Therefore, any forthcoming regulatory framework for midwives would need to be able to demonstrate that midwives are competent and safe through the publication of data collected by way of vigorous audit and research. In doing so, both the midwifery profession and the broader public would then have confidence that the new mechanisms for the regulation of midwifery are protecting the public as the legislation intended.